In this month’s thinkerview we get to know Noa Meron, our newest Senior Sustainability Specialist. Originally from Israel, the LCA expert recently arrived on New Zealand shores to join our growing product sustainability team. Noa shares her diverse experiences from over ten years working on LCA, her thoughts on our collective responsibility to protect our planet and compares life on this side of the globe.

What drew you to a career in sustainability and life cycle assessment (LCA)?

From an early age I was interested in the environment. I remember looking at the view and imagining what it was like before man came. But I never thought that protecting the environment could be my job.

From an early age I was interested in the environment. I remember looking at the view and imagining what it was like before man came. But I never thought that protecting the environment could be my job.

I like logic and math and so I thought that was a good combination for electronic engineering. After university I joined a large technology company as part of the team developing the next generation of Wi-Fi. Even though I was just starting my career there as an engineer, I felt a lot of responsibility for developing something that could potentially harm people. I think generally in humanity everyone (including big companies) is expecting our biggest problems will be solved by someone else, which can lead to ignoring some ethical questions.

I could definitely see the importance of the Wi-Fi project, but I decided that I could not continue working there. It was a values-based decision to change careers — I knew it was going to be either social or environmental sciences. It took me another year to figure it out! I studied a Master’s in environmental engineering and sustainable development at Imperial College London. We had a couple of lessons on LCA where we were introduced to the methodology.

I have huge gratitude that I found LCA. Now in my new job at thinkstep-anz I can combine LCA with my skills and strengths from programming and understanding models. LCA is similar to programming. I really believe in what it can do — to help make decisions based on data, not intuition or greenwashing.

It really improves decision making, especially as LCA has many applications.

You’ve recently made the big move from Israel to New Zealand. What similarities and differences have you noticed so far with the uptake and recognition of LCA?

Israel and New Zealand are both small, population-wise. Just like New Zealand, Israel is an exporter. It’s when Israeli companies export to Europe or America that interest in LCA increases. In New Zealand, LCA seems more developed. There seems to be a lot more LCA work in New Zealand and there is the opportunity to launch forth in the industry. There are definitely more EPDs here; in Israel there are only a few published.

In both countries there is a lot of interest from the public, but in Israel it stays there. The New Zealand government seems to take more responsibility for the environment.

Can you explain more about your diverse experience in LCA?

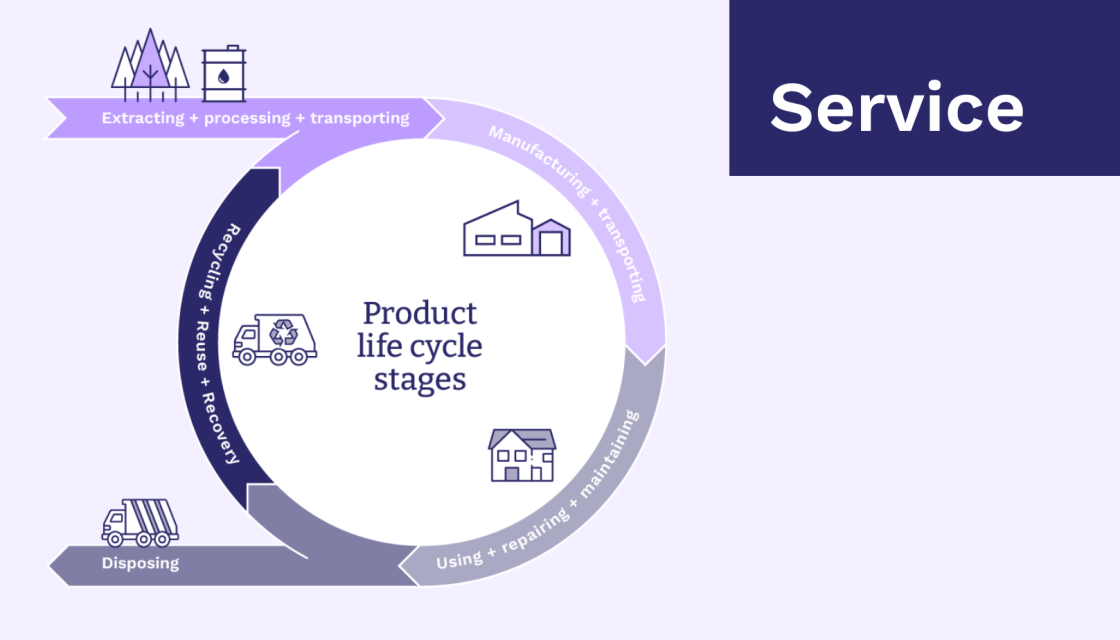

I’m lucky to have worked on LCA both in academia and outside it. In academia I had the opportunity to work on forward-looking projects. For example, I was the LCA analysis leader in a pan-European project which aimed to identify potential “servicing” policies in three sectors: water, mobility, and agri-food. Working in industry, the work has been much more output oriented. For example, I compared food packaging options for premium products of a large Israeli food company.

I also worked on an LCA for the state-wide water supply system in Israel, including treatment plant, desalination plants, and distribution system. In addition, I’ve done projects in the textile industry, personal care, automotive, agriculture, and food service.

So, my work experience has been quite diverse. This is very cool, as I’m interested in all the different aspects of environmental issues, and anything related to LCA or environmental accounting. In each industry that I’ve worked in, I got to experience different aspects of LCA.

Tell us about the LCA study you worked on where you compared the impact of reusable and disposable food containers used in kindergartens?

It started as quite a small project —a local NGO wanted to convince a city council to reduce waste at kindergartens. In Israel, kids are provided a hot lunch packaged in individual containers for each child, generating huge amounts of plastic waste every day. It was a great project, as it was not just the packaging, but the entire logistics chain. The project was a success and started a movement with many cities announcing they would change to reusable containers.

I believe the success of the study came from having a good method and a clear explanation of what was evaluated. As always with comparative LCA, there’s no single perfect answer. Some kindergartens decided to buy dishwashers to save time hand washing the containers. From an environmental perspective it wasn’t the easiest decision. There were a lot of variables, such as if the tap was left running, how the water was heated; it’s a lot about the behaviour of the kindergarten staff. I was surprised that the impact of the big commercial dishwashers depends on the way they are used, and that they are not always used wisely.

As a result of this study, I was interviewed for an article about home dishwashers in Israel’s most respected and influential newspaper. It was great to see that LCA could be really useful for people at home; to inform them on how they could improve. It was amazing to see how many people were interested. The impact of dishwashing (by hand or dishwasher) always depends on the user. There are always ways to improve, and having information from LCA helps us do this.

How did you apply your research on LCA methodology while working on the impact of Israel’s water supply system?

My PhD was about how to use the LCA methodology in different contexts and how can we localise data. LCA is data intensive. We rely on data from different locations but it’s not necessarily accurate. My PhD required cutting edge technology such as machine learning. I used water as a case study and showed that water systems can be very different; I compared LCA studies from different locations to show how variable it is.

For example, Israel’s water system is so different to New Zealand’s — a big proportion of the water comes from desalination. The five different desalination plants and the 20 or more regional water authorities meant there was a lot of data collection. If Israel had a cleaner electricity mix, it would make water usage far less impactful.

In a broader sense, what does sustainability mean to you? Where do you think we should be focusing our efforts (as individuals, businesses, countries)?

I think it’s human nature to aspire for a better quality of life for ourselves and our kids. But we need to start looking for less, which isn’t intuitive. Less consumption and travel. We need to look at our own decisions rather than thinking the government will solve it all.

All aspects of sustainability are important to me. I actually think we should be focusing on all of it! Sustainability is not only about the environment but also about social issues, such as equal rights. Personally, I relate most to biodiversity.

I have the strongest feelings for animals. Even though carbon takes the biggest share of attention (which I totally understand), I think we are forgetting that we’re all connected. Without bees, for example, we cannot survive. Carbon isn’t the only thing affecting life.

I’ve acted as a scientific advisor at the Israeli Ministry of Transportation and Road Safety. It was a great place to see the impact government can have. When working on very large and long-term projects, it is easy to remove environmental considerations, as they seem less important. I therefore initiated a sustainbility forum for all large Israeli infrastructure companies, to help them work together, and to learn and be inspired by different initiatives.

Having worked with large companies such as IBM, what appeals to you most about working in a growing sustainability business in New Zealand?

Small businesses have the ability to make change happen and be responsible for what they are offering. They are faster in decision making and can make ethical decisions more easily. In big companies it is sometimes harder to see one person’s ability to make a change, but it is possible. If a local decision can filter upwards or horizontally, it can have a huge impact. Naturally, it is easier in a smaller company. At thinkstep-anz I feel responsible. It’s a collective feeling of responsibility we are carrying.

Are there any cultural elements of sustainability from Israel that you would like to see in action here or vice versa?

I really like how many things are reused here. Someone’s waste is another’s treasure. There’s a strong sense of looking after nature. This comes from the government but is also part of the culture. It is very common to see signs here like, ‘take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints.’ I’d love to see more of this in Israel.

From what I’ve noticed so far (and this is not data-based!), recycling and waste treatment here is not as encouraging. Israelis are also much more aware of water usage. I think it is because New Zealand is far less populated, and New Zealanders have a feeling that land and natural resources are limitless. In Israel, more than 95 percent of homes have solar water heating. You don’t see these kinds of systems here.

What’re the most sustainable and unsustainable things you’ve done recently?

The most unsustainable thing would have to be travelling from Israel to New Zealand and the packaging waste produced during managed quarantine. Every meal came in at least 5 plastic containers.

The most unsustainable thing would have to be travelling from Israel to New Zealand and the packaging waste produced during managed quarantine. Every meal came in at least 5 plastic containers.

Three years ago, we built our own house in Israel from hemp (‘hempcrete’ — a mix of hemp fibre and limestone). Israel is very hot and very humid. Hemp is a great natural insulator but enables the walls to ‘breathe’ and to remove excess humidity. As a result, we hardly used air conditioning, despite the heat.

For heating we used a wood-burning mass heater that was very efficient and kept the house warm for many hours. Our annual electricity bill was less than my monthly bill in New Zealand. We also built a composting toilet and installed a system that turns our kitchen waste to biogas for cooking. Here, at a rented home it is very frustrating not to be able to optimise my actions.

Moving here was hard, not only because we had to say goodbye to our family and friends but also because we had to say goodbye to our house!

Outside of work life, what are you interested in getting involved in here?

I’m really interested in traditional arts using natural materials, like basket weaving. The local materials I used in Israel include things such as fibre from palm tree leaves. I wish to learn more about materials used for basket weaving here.

I’m really interested in traditional arts using natural materials, like basket weaving. The local materials I used in Israel include things such as fibre from palm tree leaves. I wish to learn more about materials used for basket weaving here.

Other than that, I’m really interested in the community and like to be involved in my kids’ Steiner school (I have three children). I also really enjoy travelling and camping. I’m excited to explore New Zealand!